As an unseasonably cool easterly wind from the Syrian plateau whipped around him, Roni Mansur clambered up the back of his old tank.

Decades ago, manning the Centurion tank, or Sho’t in IDF parlance (Hebrew for “whip”), Mansur had seen something far more sinister approaching from the east: Syrian armor moving into the Golan Heights. The tank was part of a badly outnumbered IDF force, engaging in a desperate battle to hold back the massive assault.

But that fight was 50 years in the past. Exactly 50 years, in fact. Today, the vehicle sits rusting in the firing position in which it was knocked out of service on the first night of the Yom Kippur War, on October 6, 1973. The metal carcasses of its victims still lay motionless on the yellow grass below.

Mansur, a 69-year-old tech CEO, has also changed in the half-century that has passed since he served as a young tank driver who unexpectedly found himself staring down massed Syrian divisions churning slowly toward his position.

“Things aren’t what they were,” he said of his physical prowess, after reaching the turret with impressive dexterity for a man approaching his seventh decade. “I can’t jump on anymore.”

Mansur began the war in 1st Platoon, G Company (Pluga Zayin) of the 188th Armored Brigade’s 74th Battalion, defending a small border position called Outpost 111. Ahead of the war’s 50th anniversary, he and Moshe Kahalani, a loader in the same platoon, took The Times of Israel back to same battlefield — and to the very tanks — in which they spent the harrowing first day of a war for which they received no advance warning.

Yom Kippur War veteran Roni Mansur walks toward the tank he fought in during the first day of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, September 13, 2023 (Lazar Berman/Times of Israel)

As the state marks the 50th anniversary of a war that changed Israel in indelible ways, the two veterans say they don’t care much about the ceremonies.

Carrying the memory of their many fallen comrades and a love for the country they defended, they are instead driven by concern for a society they say is splitting itself apart.

“It doesn’t interest me at all whether the country marks it or doesn’t mark it,” said Mansur. “The country needs to deal with things that are more pressing than ceremonies.”

Battle days

Mansur, the son of Iraqi immigrants, had joined the company less than two months before Yom Kippur 1973. Kahalani had been there for a year, and already had under his belt a “battle day” against the Syrians — one of the short but intense encounters that occasionally erupted between the opposing sides.

The young soldiers — then stationed in Nafah, the main IDF base on the Golan — saw some signs of heightened alert on the eve of Rosh Hashana, 10 days earlier. They were excitedly getting ready to head home for the holiday, then noticed a helicopter landing at the base. They sensed the sudden arrival of a senior officer did not bode well for their chances of being released, and they were correct.

“We were told there’s no going home, go back to your tanks,” recalled Mansur. G Company’s 1st Platoon was sent to Hushniyeh, a small base next to an abandoned Syrian village about three kilometers from the border. The other two platoons were sent to positions further north along the line.

Yom Kippur War veteran Roni Mansur (in white) at the Hushniyeh base, September 13, 2023 (Lazar Berman/Times of Israel)

The company was temporarily placed under the command of the brigade’s other battalion, the 53rd, meaning that the tank commanders were barely familiar with their higher-ups.

During the war of attrition, which ended three years earlier, Israel had set up a series of outposts on the volcanic cones along the ceasefire line. The positions ran south from Outpost 100 in Mount Dov to 117 near Ramat Magshimim.

With Israeli civilians already settling points near the frontier and only a short distance separating Syrian positions from bridges over the Jordan River that would be crucial for any possible counterattack, the IDF could ill afford any enemy advance past the ceasefire line; troops in the outposts had to be ready to fight to hold onto every inch on the plateau. In the case of a Syrian assault, the outposts were meant to spot for artillery, and hold back the advance for a day and a half until Israel’s reserve divisions could be brought into the fight.

Illustrative: View of the Israel-Syrian border near Tel Saki, Southern Golan Heights, on September 15, 2021. (Michael Giladi/Flash90)

In case of fighting against Syria, Mansur and Kahalani’s platoon was tasked with rushing to Outpost 111, which controlled one of the main avenues where enemy vehicles could speed into the heart of the Golan.

They remained in Hushniyeh over the next 10 days, occasionally heading over to 111 and patrolling the sector.

Things remained calm as the young crewmen prepared for the Yom Kippur fast. The soldiers looked forward to breaking the fast on ice-cold sodas they had stored away in the commissary’s freezer.

Things got a little more tense as the sun began to set. The soldiers were about to sit down for their pre-fast meal when word came down that the IDF chief rabbi had given orders for the fast to be postponed. They were not told why, but the unorthodox order gave the soldiers reason for concern.

They ate after sundown two hours later, then began the fast.

At about 9 p.m., Battalion Commander Yair Nafshi arrived at Hushniyeh, and called the platoon into the dining room.

He told the assembled tankers that the alert level was being raised in anticipation of a limited Syrian assault the next morning — referred to as a battle day. Syria might even try to capture a small piece of territory, he said.

“We didn’t get too worked up,” Mansur recalled 50 years later, standing among the crumbling buildings of the old Hushniyeh base. “Go up to the ramps, fire, come back in the evening. Everything is fine. At that point, the brigade was very experienced in battle days.”

“I remember no one took it too seriously,” he said.

Later that evening, they were told to sleep with their coveralls and boots on. “Okay,” said Mansur, “this was starting to smell like something is not okay here.”

Israeli troops rushing up to the northern frontier with the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, October 7, 1973. (GPO/Eitan Harris)

On the morning of October 6, Yom Kippur day, the soldiers were instructed to move the tanks outside of the base and have them ready to rush up to 111. They spent the morning being hurried to their tanks, then being sent back.

“The last time we went to the tanks was about 1 p.m.,” remembered Mansur. “Then they told us to spread out orange panels for identifying armor, then we painted white lines on the back of our tanks so the air force could identify us.”

By 1:30 p.m., the crewmen were again relaxed, coveralls half open, thinking about the cold drinks waiting for them at the end of the fast.

War

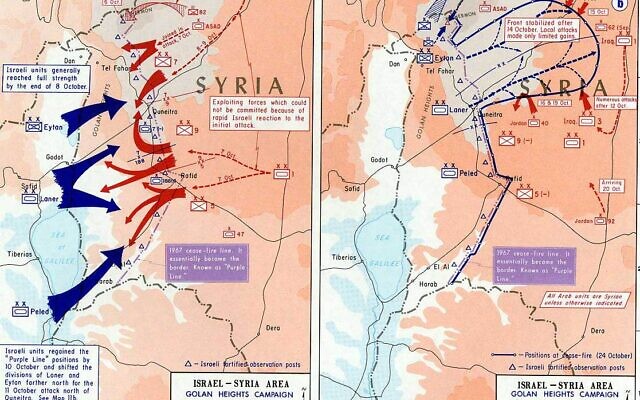

Meanwhile, the Syrian 9th Division was finishing final preparations for its assault on the center of the Israeli defensive line, and the bases and road junctions beyond. Israel’s political leadership had received ample warning about Egyptian and Syrian plans to invade, but chose to forgo the opening strike that shattered Arab plans in 1967 for fear of losing US support.

The 9th Division’s infantry brigades were tasked with capturing the Israeli line of outposts within the first two hours of the invasion, to allow the armored elements to push deeper into the Golan.

An IDF soldier looks at a Skyhawk warplane in the Golan Heights during the Yom Kippur War, October 1973. (State Archives)

In all, Israel had only 177 tanks on the Golan, which faced some 1,400 Syrian tanks and another 115 artillery batteries. The 188th Brigade drove the 52-ton Sho’t tanks, which were heavier than the Syrian T-55s and T-62s, and could carry far more ammunition. But the Soviet-made armor massing on Israel’s border was quicker, had larger cannons, and had the significant advantage of night vision.

At 1:55 p.m., the soldiers of G Company’s 1st Platoon, lounging on their vehicles, were given rude notice that they were at war when two Syrian MIGs sped by only meters above them. Sixty other Syrian planes attacked Israeli positions across the Golan at the same time.

“We jumped into the tanks,” Mansur said. “A few seconds later, an artillery barrage began. There was not a stone that didn’t jump. It was crazy.”

The four tanks at Hushniyeh — commanded by company commander Uri Akavia, platoon commander Dan Oberlander, platoon sergeant Tzvi Mizrahi and tank commander Yair Deutsch — sped toward their outpost.

Mansur, whose scheduled leave had been canceled as a punishment, was driving Deutsch’s tank. Kahalani worked as a loader in Akavia’s tank.

“Those crazy drivers got us up their quickly and we took our positions,” explained Kahalani, now standing in the firing position next to Outpost 111 after driving up from his old base at Hushniyeh.

He remembers the driver, Avi, exclaiming to Akavia on his tank’s internal radio as they got their first view of the Syrian array, “Uri, this isn’t a battle day. Look at all the tanks!”

“We are starting to react at the beginning, giving orders,” said Kahalani. The Syrian tanks sat stationary for the first few minutes as the experienced Israeli crews started destroying them one by one.

“One of the advantages we had was that we worked like a well-oiled machine,” explained Mansur. “Go up, put in a shell, target, fire, another shell, another target.”

“Every first or second shell was on target.”

Then the Syrians started to advance.

As the four Sho’t crews worked furiously, Shmuel Askarov, the deputy commander of the 53rd Battalion, broke into the platoon’s communications.

“Uri, take yourself and two more tanks and go down toward Tel Kudna,” he said, desperate to plug a Syrian advance to south of 111.

Akavia protested to Askarov, who had been temporarily in charge of the company for only 10 days.

“If I leave here, I don’t have any protection,” Akavia insisted. “I don’t have a firing position there.”

“I don’t care, we need to be there before they take it,” Askarov responded.

Akavia, with two tanks following, headed south, leaving Mansur’s crew alone.

The three tanks continued the fight in their new, far more exposed, position.

“Suddenly, it was quiet,” said Kahalani.

“The driver Asher says in the internal radio, ‘Guys, I’m calling to Uri, why doesn’t he answer?’” said Kahalani,

“I look over at Uri — we hadn’t felt anything unusual in the tank — sitting in his seat, without a head.”

The wire of one of the dangerous new Sagger anti-tank missiles had sliced through the neck the company commander, who was expected to keep his head outside the tank in order to better control the battle.

“Then I look,” Kahalani remembered, “and at my feet I see his head.”

“We immediately recovered,” he continued in an even tone. “Asher and I took the body, placed it beside me next to the shells. Then Asher and the gunner and I continued to fight. I load, he fires. I load, he fires.”

Others were hit as well. To his left, Kahalani saw Mizrahi jump out of his tank in flames. “He was screaming in pain. We couldn’t do anything.”

A gunner named Mansbach was hit by a bullet. The driver, Zion Sharabi, managed to pull Mansbach out of the turret and drag him into a ditch to perform life-saving first aid.

“No one stopped fighting,” said Kahalani. “You have to keep going. There’s no pause.”

“Fifty years later,” he continued calmly, “I still get asked how I can just explain everything that happened and how Uri was killed, step by step. I don’t have a psychological explanation, but I guess I’m still broken.”

Kahalani’s efforts to hold back the Syrians in that exposed position ended at 5:30 p.m., when his tank suffered a direct hit from a Sagger missile and couldn’t drive or fire. The survivors waited until dark, then ran toward Alonei Habashan junction. They were scooped up by the brigade’s deputy intelligence officer in an armored carrier.

Kahalani told the officer that they were trying to get back to Hushniyeh, unaware that their base had already been overrun, and its occupants captured. They would be later be found blindfolded and handcuffed, executed by Syrian forces.

Kahalani and the surviving tankers were taken to Nafah, and were soon put in new crews as reservist units began arriving.

Alone

Meanwhile, Mansur’s tank had continued fighting alone.

“It’s hard to explain what it is to be alone up here,” he said.

Night fell, and without night vision, the Israelis were fighting blind. Mansur, as driver, had a device that could pick up on the T-55 infrared beams, used for aiming at night.

He looked in, and saw a beam moving up the road toward 111.

It’s hard to explain what it is to be alone up here.

“I see the beam and I start to yell that there’s a tank coming up our way,” said Mansur. “We had a shell in the cannon. The tank turns, and the beam is on me. If the beam is on me, it means the cannon is on me. It can’t miss. I start yelling, ‘Fire! Fire!’ The gunner couldn’t find the tank because his light on his sight was burned out.”

“I told him there’s nothing to see, it’s 20 meters away.”

In the crosshairs of an enemy tank, Mansur was about to hit the gas and ram the T-55. Suddenly, he felt his tank jump, and saw a shell hit the Syrian vehicle.

The tank that Roni Mansur fought in on the first day of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, September 13, 2023 (Lazar Berman/Times of Israel)

He reversed his tank quickly, but the machine broke down, leaving it where it still sits today.

Mansur and the other three crew members waited next to Outpost 111 in the dark for someone to pick them up, not knowing if a Syrian or Israeli tank would get there first.

After midnight, an IDF tank rolled by. The four tankers clambered in, sitting on each other with Mansur at the bottom. “I was the youngest,” he said with a laugh.

The commander of the rescue tank told the guests that they would pass through an enemy column to reach Nafah, and that they needed to remain silent.

Soldiers pose on top of a tank during the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War on October 6, 1973. (Avi Simhoni/Bamahane/Defense Ministry Archives)

“I asked myself if this guy was shell-shocked,” said Mansur. “Why be quiet? There’s a tank engine here. My voice is what will wake up the Syrians?”

Somehow the tank made it to Nafah, from there, Mansur was taken off the Golan to be assigned to a new company and new tank.

Two more of his tanks were knocked out over the next three weeks as he pushed into Syria as part of the Israeli counteroffensive there.

Aftermath

In the 50 years since the war, retrospective books and movies have largely focused on the decisions made by those at the highest levels of the state — Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, Chief of Staff Dado Elazar and the generals battling on both fronts.

Rendered anonymous are the young tankers and infantrymen whom Kahalani thinks deserve credit for saving Israel from being overrun.

“The bulk of the war was fought by the soldiers,” he said. “It’s nice to talk about the commanders, but we didn’t have a brigade commander, or deputy brigade commander, or company commander, or platoon commander.”

188th Brigade Commander Yitzhak Ben-Shoham, his deputy David Yisraeli, Akavia, and Oberlander all fell stopping the Syrian onslaught in the first days of the war.

Yom Kippur War veteran Moshe Kahalani walks to his Sho’t tank near Outpost 111 in the Golan, where he battled Syrian forces 50 years ago today. pic.twitter.com/4T7BPg0bgc

— Lazar Berman (@Lazar_Berman) October 6, 2023

“In the end, the ones who did the work here are the simple soldiers,” Kahalani argued. “The crews that fought. The time has come to recognize them. They’re the ones who stayed there, did the work, and succeeded in holding back the Syrians until they were hit.”

What credit the political leadership gets for its handling of the war is hardly laudatory.

Both Kahalani and Mansur accuse politicians of being willing to trade the lives of the soldiers in order to remain in Washington’s good graces by foregoing a preemptive strike.

“But people still fought shoulder to shoulder,” Mansur noted. “It didn’t matter who you are or what you think.”

Six years before the war, Mansour was among the first to celebrate his bar mitzvah at the Western Wall, just weeks after it was captured. But the Yom Kippur War largely exposed erased the high of the Six Day War’s lightning victory, becoming a darker inflection point for the nation.

“It was a dramatic change from the blind faith people gave to the political leadership before,” Mansur said. “After the war, there was a major crisis in the state when a lot of people understood a large portion of the deaths in the war could have been prevented.”

Sitting on the exposed rocky outcropping where Akavia and Mizrahi fell, the veterans now see the country again being rocked by a crisis that is changing the country in far-reaching ways, expressing deep concern — and no small amount of anger — over the anti-government protests rocking the country.

People still fought shoulder to shoulder. It didn’t matter who you are or what you think.

Kahalani lamented the divisions being wrought by the massive demonstrations against attempts by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government to overhaul the judiciary. Army veterans have taken a leading role in many of the protests, and reservists have sparked worries with threats to freeze volunteer commitments.

“I am worried by what’s happening now,” Kahalani said. “All the demonstrators who fought in wars, to see them on the other side trying to put a spoke in the wheels of the country, I am worried, I am angry.”

“I respect everyone who has an opinion even if it isn’t my opinion,” he continued. “But everyone has to have red lines, what is forbidden to do. The country is all of ours.”

They expressed particular ire over the Yom Kippur War veterans who stole a Sho’t from the Golan in February to protest the Netanyahu government’s proposed reforms.

A Sho’t tank that was taken from the Tel Saki memorial site in the Golan Heights, by veterans of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, to protest the government’s planned judicial overhaul, February 16, 2023. (Michael Giladi/Flash90)

The tank had been helmed by F Company commander Avi Ronis, who was killed in combat. Kahalani and several others had dragged Ronis out, “cleaned the turret of his blood,” and gone back inside to continue fighting.

“I write and I shout. Avi Ronis is spinning in his grave,” he said. “Who gave you the right?”

Mansur took issue with Yom Kippur War veterans protesting under that flag, as if everyone who fought in the war stood on the same side politically.

“I don’t think it’s right to split the nation, and definitely not to speak for 1973 veterans. Here you have 1973 veterans for the reform. We don’t go out with flags and drums and we don’t use the veterans of 1973 label.”

Mansur said the focus should be on bridging the disconnect between the camps, and to ensure protestors don’t cross red lines.

“To attack the car of a minister, it’s unthinkable. And I am very sorry that people take the law into their own hands, it’s something that cannot be done,” he said. “Remember there’s another side, that is sitting on the side, and is taking responsibility.”

With that, the two aging warriors started the walk back down to the car below, sharing stories the whole way down.

Behind them, on the hill, their tanks faced into the wind, their barrels still pointing east toward Damascus.